Flux, what and why?

If you are into front-end development, you’ve probably heard or read the term ‘Flux’. What does it mean and why should you care?

Let’s get one misconception out of the way, Flux is not a framework. It is a design pattern, an idea. It describes how to manage state and how data should flow through your application.

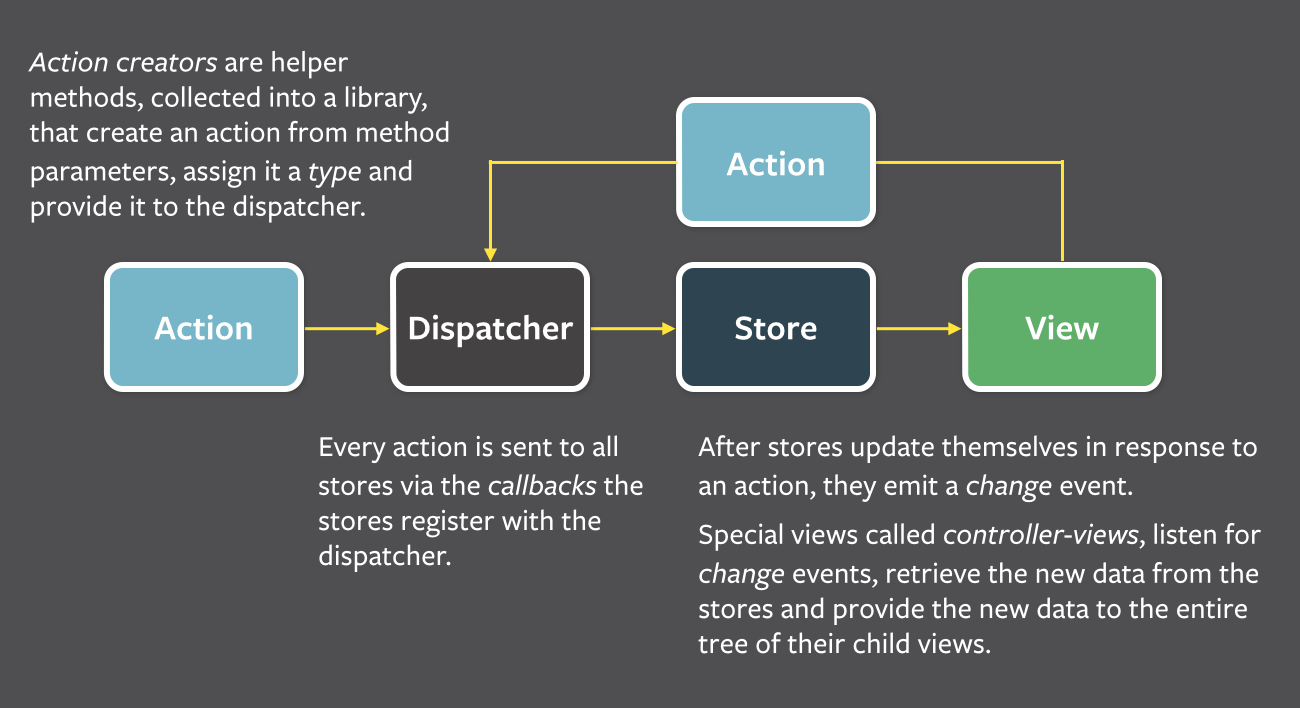

The core principle is that there is a ‘unidirectional data flow’. Data always flows in one way, this makes rich web applications more manageble.

Flux was presented by Facebook in combination with React. However, it is not required that you use React, you can use anything as View layer. Also there are lots of varieties and implementations out there. In this article we will focus on the ‘original way’ Facebook presented it, the examples will be in EcmaScript 6, they are slightly simplified but still valid.

The reason why React works so well with Flux is because it also follows the unidirectional data flow principle. Frameworks like AngularJS use concepts like two way databinding which violate this principle.

Actions

The pattern starts with Actions. Actions are essentially ‘events’ that happen in you application. They have a type and optionally some data. Actions can come from Views, other Actions or the Server. Actions are fired by calling an Action builder which is just a function. That function sends a new Action to the Dispatcher.

import Dispatcher from './dispatcher';

import { ADD_MESSAGE } from './constants';

export function addMessage(message) {

const action = {

type: ADD_MESSAGE,

message: message

}

Dispatcher.handleAction(action);

}First we import a reference to the Dispatcher and the constants that contain our action types. When a user calls the addMessage() Action builder function it will send a new Action object to the Dispatcher with its handleAction() method. From that moment the job of the Action builder is done, fire and forget.

Dispatcher

The Dispatcher is the central ‘hub’ so to speak of a Flux application. The Dispatcher receives Actions and dispatches them to all the Stores. This is the only part that Facebook’s implementation provides you the code for. I’m not going to give a complete code example but I will show you the general interface:

class Dispatcher {

register(callback) {

//The Stores use this method to receive actions

//the callback gets called when an action happens

//with that action as parameter

}

handleAction(action) {

//The Action builders call this method to get their

//action dispatched to the stores

}

}Most implementations of Flux remove the Dispatcher. In practice it’s just a kind of event system and there are simpler ways to distribute Actions.

Stores

Stores hold the state of the application. They receive Actions from the Dispatcher. The most important rule is that nobody but the Store itself may ever change its state! When the Store receives an Action from the Dispatcher, it can decide on what to do depending on the Action’s type and data. Finally, the Store notifies the View when its state has changed.

import { List } from 'immutable';

import EventEmitter from 'event-emitter';

import { ADD_MESSAGE, CHANGE_EVENT } from './constants';

import Dispatcher from './dispatcher';

let messages = List();

class MessageStore extends EventEmitter {

constructor() {

this.registerAtDispatcher();

}

getMessages() {

return messages;

}

emitChange() {

this.emit(CHANGE_EVENT);

}

addChangeListener(callback) {

this.on(CHANGE_EVENT, callback);

}

registerAtDispatcher() {

Dispatcher.register((action) => {

const {type, message, data} = action;

switch(type) {

case: ADD_MESSAGE: {

const message = {

message: message,

date: new Date()

};

messages = messages.push(message);

this.emitChange();

break;

}

default: {

break;

}

}

});

}

}

export new MessageStore();Firstly, the state is declared in a variable outside of the Store to hide it from outsiders. Then we register the Store at the Dispatcher with a callback. Everytime the Dispatcher receives an Action this callback is called. If it is called with an Action of type ‘ADD_MESSAGE’ we add a message to the messages list and notify the Views.

The only way for outsiders to read the messages list is by calling getMessages() on the Store. They can get notified for changes by registering a callback with the addChangeListener() method. This implementation uses the event-emitter library to add this event functionality.

In this example I use ImmutableJS to make the messages list Immutable. When I push a message to the list, it doesn’t mutate the original list, rather it returns a new list with the new message added. You are not required to use ImmutableJS, but I recommend never mutating data in your application so your data flow is simple and predictable.

Views

The View can be anything. It can be a React component if you use React. But it can also be an Angular component or whatever. A View registers itself at a Store (or multiple). When the Store updates itself it will notify the View and the View will update itself with the new state. The View can also trigger Actions, for example when the user clicks a button.

import React, { Component } from 'react';

import { addMessage } from './message-actions';

import MessageStore from './message-store';

export class MessageView extends Component {

constructor() {

this._onMessagesUpdated();

}

componentDidMount() {

MessageStore.addChangeListener(() => this._onMessagesUpdated);

}

_onMessagesUpdated() {

this.setState({ messages: MessageStore.getMessages() });

}

_handleAddMessage(e) {

e.preventDefault();

const message = React.findDOMNode(this.refs.messageInput).value;

addMessage(message);

}

render() {

const messages = this.state.messages.map((msg) => <li>{msg.message}</li>)

return (

<div>

<ul>{messages}</ul>

<input type="text" ref="messageInput"/>

<button onClick="this._handleAddMessage">Add</button>

</div>

)

}

}This is an example of how a View could look in React. I won’t get into the React specific details. When the component mounts it registers itself at the Store with the _onMessagesUpdated() callback. When the Store changes, it will call this callback and the View will retrieve the latest messages. So far the receiving part.

A View however can also put new data into the application. But it cannot go straight back to the Store, this would violate the unidirectional data flow. It can do so by triggering Actions. This View does this in the _handleAddMessage() method. When the user inputs a message and clicks the ‘Add’ button, this handler will be fired and trigger an ‘ADD_MESSAGE’ action, then the cycle begins all over again!

Conclusion

This article became larger then I aimed for, this is mostly because Flux introduces a bunch of concepts that might seem a bit overkill. Some of them might actually turn out to be superfluous, as many implementations prove. Nonetheless Flux is a very simple concept once you wrap your head around it. It makes your application scaleable and its behaviour predictable. It is encouraged for ‘larger’ applications but I would even recommend it for ‘smaller’ ones. Using a framework like Alt or Redux gets rid of most of the boilerplate. Just try it out and let me know what you think!

Reference

- The ‘official’ Flux website: facebook.github.io/flux

- Nice video on using the Alt Flux framework: youtu.be/0wNWjtp-Ldg

- A collection of frameworks/implementations of Flux: github.com/voronianski/flux-comparison

Niels Gerritsen

·

Niels Gerritsen

·